Maple trees offer far more than spectacular autumn foliage and shade—nearly every part of these remarkable trees provides edible resources that humans have harvested for centuries. From the sweet sap flowing through their vascular systems to the nutritious seeds dispersed each spring, maples represent a complete food source that connects us to traditional ecological knowledge and sustainable foraging practices.

The Vascular Architecture: Understanding Maple Sap Production

The circulatory system of maple trees operates through a sophisticated pressure-driven mechanism that makes sap harvesting possible. During late winter and early spring, when daytime temperatures rise above freezing while nights remain cold, maples generate positive pressure within their xylem tissues. This physiological phenomenon occurs because freeze-thaw cycles create pressure differentials that force sap upward from the root system.

Sugar maple (Acer saccharum) produces the highest sugar concentration, typically ranging from 2% to 3% sucrose content, though this varies based on soil composition, tree age, and seasonal conditions. Red maples (Acer rubrum), silver maples (Acer saccharinum), and box elder (Acer negundo) also yield harvestable sap, though with lower sugar concentrations requiring longer boiling times. The sap itself contains not only sucrose but also trace minerals including calcium, potassium, manganese, and various organic acids that contribute subtle flavor complexities to finished syrup.

Commercial and home-scale sap collection involves drilling shallow tap holes approximately 2 to 4 inches deep into the sapwood layer, avoiding penetration into the heartwood. A single mature maple with a diameter exceeding 12 inches can support one tap, while larger specimens may accommodate multiple taps without compromising tree health. The traditional ratio remains consistent: approximately 40 gallons of sap reduce through evaporation to produce one gallon of finished maple syrup.

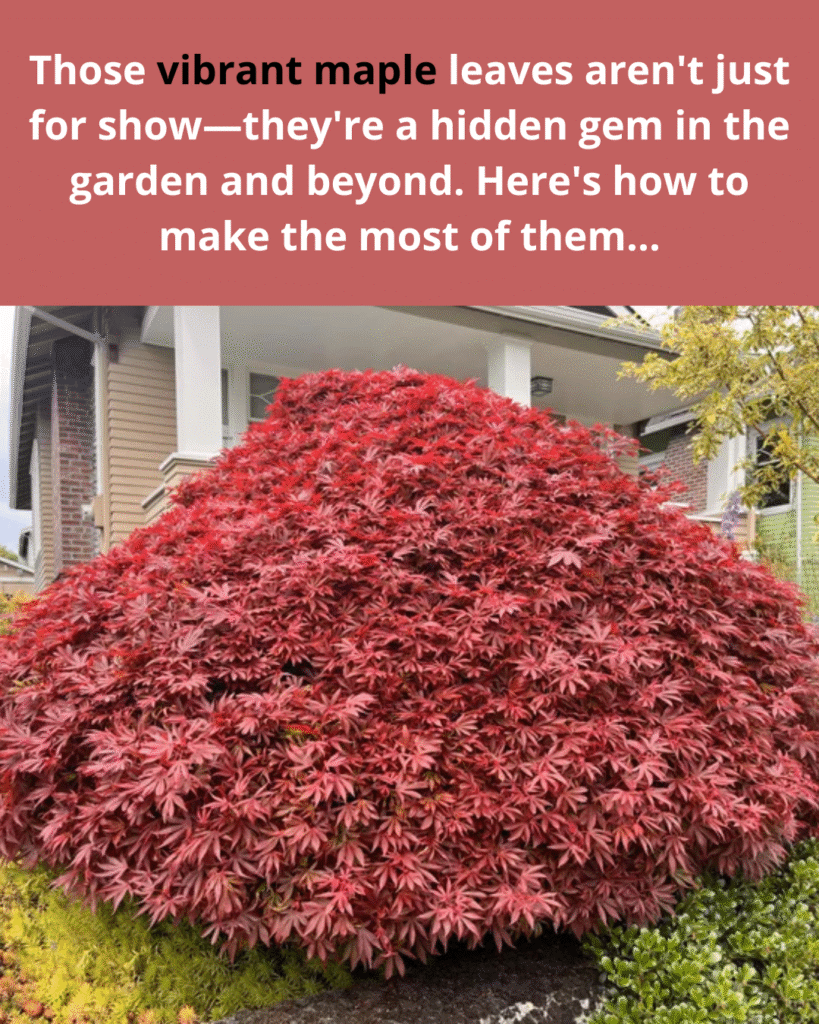

Foliage Utilization: Nutritional Components and Culinary Applications

Young maple leaves emerging in spring contain edible qualities often overlooked in contemporary foraging literature. These tender leaves, harvested before full maturation and lignification, offer a mild, slightly sweet flavor profile. Traditional Indigenous practices included consuming young maple leaves raw in small quantities or incorporating them into cooked preparations.

The chemical composition of maple leaves includes flavonoids, tannins, and various polyphenolic compounds. However, mature leaves develop higher concentrations of certain compounds that make them less palatable and potentially problematic in large quantities. Spring leaves, collected when still soft and light green, provide the most suitable option for human consumption. They can be blanched briefly to reduce any astringency, then added to mixed green salads or used as wrapping materials for steamed foods.

Some foragers prepare maple leaf tea by steeping dried young leaves in hot water, creating an infusion with subtle sweetness and earthy undertones. The drying process should occur in well-ventilated conditions away from direct sunlight to preserve color and prevent mold development.

Samaras: The Nutritional Profile of Maple Seeds

Maple seeds, contained within the distinctive winged structures called samaras or « helicopter seeds, » represent a significant but underutilized food resource. These seeds mature in late spring through early summer depending on species and geographic location. The papery wing facilitates wind dispersal, while the seed itself contains a nutritious embryo rich in proteins, fats, and carbohydrates.

Harvesting samaras requires timing—collect them when the seeds have developed full size but before the wings dry completely and dispersal begins. The ideal window spans approximately two to three weeks. Young, green samaras possess a tender texture and require minimal processing, while more mature seeds develop harder seed coats necessitating longer cooking times.

Preparation methods vary across cultures. Boiling removes any bitterness from the seed coat while softening the embryo for consumption. After boiling for 15 to 20 minutes, the seeds can be drained, seasoned, and roasted to develop nutty flavors. Some preparation techniques involve removing the wing structure and seed coat after boiling, consuming only the inner embryo. The taste resembles a cross between fresh peas and cashews, with a slightly sweet, vegetal character.

Nutritional analysis reveals that maple seeds contain approximately 3% to 4% protein and modest amounts of healthy fats. They also provide dietary fiber and small quantities of minerals. While not as calorie-dense as tree nuts, samaras offer a seasonal food source that supported various Indigenous communities historically.

Inner Bark Harvesting: Cambium Layer as Emergency Food

The cambium layer—the thin, living tissue between outer bark and sapwood—provides emergency sustenance and has historical significance in survival situations. This meristematic tissue contains starches, sugars, and some proteins that make it digestible and nutritionally viable, though hardly a preferred food source under normal circumstances.

Harvesting cambium requires careful technique to avoid girdling or permanently damaging trees. Sustainable collection involves removing small vertical strips of outer bark to access the cream-colored to pale green cambium layer beneath. This practice should only occur on trees scheduled for removal or in genuine survival contexts, as improper harvesting compromises tree health and creates entry points for pathogens.

The raw cambium possesses a mucilaginous texture and mildly sweet taste with slight bitterness. It can be consumed fresh, though most traditional preparations involve drying the strips into brittle sheets that can be ground into flour or rehydrated in soups. Boiling reduces any astringent qualities while rendering the tissue more digestible. Some accounts describe roasting dried cambium to create crispy strips with enhanced sweetness.

The nutritional density of cambium remains relatively low compared to other plant tissues, primarily providing carbohydrates with minimal protein or fat content. Its value lies in accessibility during seasons when other food sources diminish—late winter and early spring when stored foods dwindle but before new plant growth emerges.

Flower Structures: Ephemeral Spring Resources

Maple flowers emerge before or simultaneously with leaf development, creating brief windows for harvesting. These small, often inconspicuous flowers vary in color from yellow-green to reddish depending on species. While not widely consumed today, some historical accounts and contemporary foragers document their edibility.

The flowers can be collected and added fresh to salads, providing subtle sweetness and visual interest. Their delicate structure means they don’t withstand cooking well, but they can be infused into syrups or vinegars to extract their mild flavor compounds. Sugar maple flowers specifically contain nectar that attracts early-season pollinators, and this sweetness translates to human palates as well.

Harvesting requires restraint—removing entire flower clusters impacts seed production for that season. Sustainable practice involves collecting only small portions from multiple trees rather than heavily harvesting individual specimens. The flowering period typically lasts only one to two weeks, making this an ephemeral resource requiring attentiveness to phenological timing.

Root Considerations and Underground Structures

While maple roots themselves aren’t typically consumed due to practical harvesting difficulties and minimal nutritional return, understanding root architecture informs sustainable above-ground harvesting practices. Maple root systems extend horizontally well beyond the crown drip line, with fine feeder roots concentrated in the upper soil layers where nutrient and water absorption occurs most efficiently.

When tapping trees for sap, the tap hole intersects xylem vessels that originate from root water uptake. Healthy, extensive root systems correlate with vigorous sap flow and higher sugar content. Soil compaction, construction damage, or other factors compromising root health directly impact sap quality and quantity.

Some ethnobotanical records mention using maple root decoctions for medicinal purposes rather than food, though these applications require significant caution and proper identification to avoid confusion with potentially toxic species.

Seasonal Timing and Phenological Awareness

Successful maple harvesting depends entirely on understanding seasonal rhythms and phenological indicators. Sap flow occurs during a narrow window—typically late February through early April in temperate regions—when temperature fluctuations create the necessary pressure dynamics. Early leafing or warm winter conditions can shorten or eliminate viable tapping periods.

Young leaves become available as buds break, generally overlapping with late sap flow. This period lasts approximately two to three weeks before leaves mature and develop less palatable chemical profiles. Flowers emerge shortly before or with leaves, creating another brief collection opportunity.

Samaras develop through spring, maturing by late May through June depending on latitude and elevation. Monitoring trees weekly during this period helps identify the optimal harvest window when seeds have developed but haven’t yet dispersed.

Cambium harvesting theoretically occurs year-round but proves most practical during active growing seasons when the layer separates more easily from surrounding tissues. However, ethical considerations severely limit this practice regardless of timing.

Species-Specific Variations in Edibility

Not all maple species offer equal edibility or palatability across their various parts. Sugar maple stands as the gold standard for sap production due to high sucrose concentration. Red maple produces adequate sap but with lower sugar content, requiring approximately 50 gallons to yield one gallon of syrup. Silver maple and box elder also provide usable sap, though flavor profiles may include subtle differences—box elder sometimes carries slight musty notes that some find less appealing.

Regarding seeds, all maple samaras appear edible once properly prepared, though size variations affect processing practicality. Norway maple (Acer platanoides), an introduced species in North America, produces larger seeds that some foragers prefer for ease of handling, despite the species’ invasive characteristics in many regions.

Leaf edibility remains relatively consistent across species when harvesting young foliage, though individual sensitivity to specific compounds varies among consumers. Tasting small quantities initially helps identify any personal tolerance issues.

Processing Techniques and Preparation Methods

Raw consumption applies only to sap, young leaves, and potentially very young seeds. Most maple parts benefit from some form of processing to improve palatability, digestibility, and safety. Boiling represents the most versatile technique, applicable to seeds, cambium, and leaves when preparing them beyond raw applications.

For samaras, an initial boiling stage removes surface debris and begins softening the seed coat. Subsequent roasting—either in a dry pan or oven at moderate temperatures around 300-325°F—develops nutty flavors through Maillard reactions while crisping the texture. Seasoning options range from simple salt to more complex spice blends depending on intended use.

Cambium processing traditionally involves scraping the layer from bark sections, then either immediate consumption or drying for preservation. Drying occurs by spreading thin layers in warm, ventilated spaces until brittle. The dried product can be ground using mortar and pestle or modern grinders, producing a flour-like substance that blends into other flours or thickens soups.

Sap reduction requires sustained heat application to drive off water content through evaporation. This process cannot be rushed—boiling too rapidly or at temperatures exceeding optimal ranges can caramelize sugars prematurely or produce off-flavors. Traditional outdoor evaporation over wood fires produces the most fuel-efficient processing, while indoor methods require exceptional ventilation due to massive steam production.

Nutritional Contributions and Dietary Context

Maple-derived foods serve better as supplementary resources rather than dietary staples. Sap provides quick carbohydrates with trace minerals, serving historically as a spring tonic after winter’s preserved food monotony. The mineral content, while modest by absolute measures, includes bioavailable forms of calcium, potassium, and manganese that contributed to nutritional diversity.

Seeds offer more substantial nutrition with their protein and fat content, though yields per harvesting effort remain relatively low compared to cultivated crops. Their value lies partly in seasonality—providing fresh food during the gap between stored winter provisions and summer’s abundance.

Leaves and cambium contribute primarily roughage and carbohydrates with minimal protein or fat. These components filled bellies and provided psychological satisfaction but couldn’t sustain populations without complementary food sources. Understanding this context prevents romanticizing historical subsistence patterns while appreciating the ecological knowledge required to utilize diverse resources effectively.

Ecological and Ethical Considerations

Sustainable maple harvesting requires understanding tree physiology and population dynamics. Sap tapping, when performed correctly with appropriate tap numbers and hole sizes, causes minimal long-term damage. Trees compartmentalize tap wounds, forming callus tissue that seals the injury over several years. However, drilling new holes each season leaves permanent internal damage points that accumulate over a tree’s lifetime.

Leaf and flower collection impacts photosynthetic capacity and reproductive output respectively. Removing small quantities from multiple trees distributes impact more equitably than concentrating harvest on few individuals. For flowers specifically, completely stripping trees eliminates seed production for that season, potentially affecting local wildlife dependent on samaras.

Cambium harvesting presents the most significant ethical concerns. Even careful techniques damage protective bark layers, creating vulnerability to pests and pathogens. This practice makes sense only in survival contexts or when trees face removal regardless. Casual or recreational cambium collection cannot be justified from conservation or tree health perspectives.

Contemporary foragers must also consider property rights, public land regulations, and invasive species management when harvesting maple resources. In some regions, Norway maple removal efforts create opportunities for extensive samara harvesting without ecological guilt, as these seeds would otherwise contribute to further invasive spread.

Traditional Knowledge and Cultural Significance

Indigenous communities across northeastern North America developed sophisticated maple harvesting technologies centuries before European contact. Archaeological evidence suggests maple sap collection dates back at least 1,000 years, with some researchers proposing even earlier origins. The technology included bark containers for collection, wooden taps or natural spouts, and ingenious evaporation methods using heated stones dropped into bark vessels.

The spring maple harvest held cultural significance beyond mere caloric contribution—it marked winter’s end and provided community gathering opportunities after months of dispersed winter camps. The resulting sugar and syrup supported preservation of other foods, sweetened medicines, and served as valuable trade goods.

This knowledge survived colonization and continues evolving through contemporary Indigenous practitioners who maintain connections to traditional practices while incorporating modern efficiency improvements. Respecting these cultural origins means acknowledging that maple harvesting techniques represent intellectual property developed through generations of careful observation and experimentation.

The edibility of various maple parts extends beyond simple sustenance into realms of cultural identity, seasonal celebration, and connection to place. Understanding these dimensions enriches contemporary engagement with maple resources while fostering respect for the knowledge systems that discovered and refined these practices over millennia.