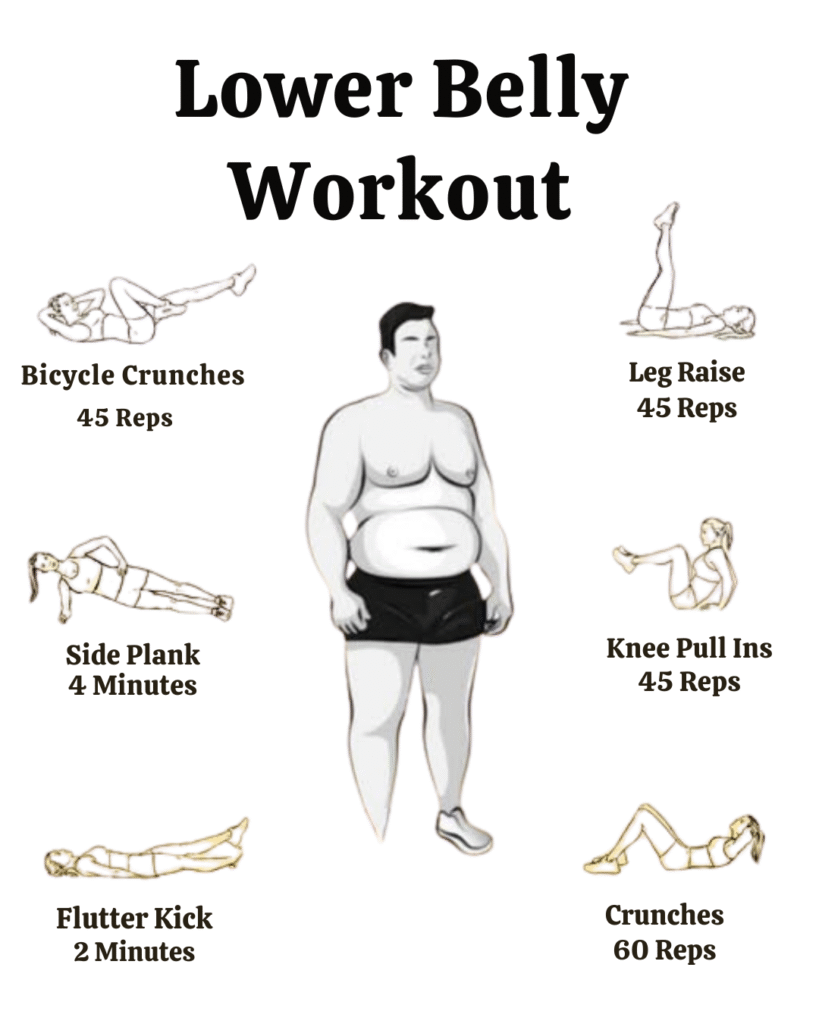

Discover the most effective lower belly workout combining targeted exercises, core activation techniques, and progressive resistance training to strengthen deep abdominal muscles, reduce visceral fat, and build functional core stability through evidence-based movement patterns.

Understanding Lower Abdominal Anatomy and Core Function

The lower abdomen encompasses a complex network of muscular structures working synergistically to stabilize the pelvis, protect internal organs, and facilitate movement. The rectus abdominis extends from the sternum to the pubic bone, while the transverse abdominis acts as a natural corset, wrapping horizontally around the trunk. The internal and external obliques create rotational capacity and lateral flexion.

What distinguishes lower belly training from general core work is the emphasis on posterior pelvic tilt and hip flexor coordination. The lower fibers of the rectus abdominis activate most effectively when the pelvis tilts backward, bringing the pubic bone toward the ribcage. This movement pattern counters the anterior pelvic tilt common in sedentary populations.

Research demonstrates that isolated « lower ab » exercises don’t exist in pure form—the rectus abdominis contracts as a whole unit. However, certain movements create greater activation in the lower region through biomechanical positioning and load distribution. Studies using electromyography show reverse crunches and leg raises generate higher activity in the lower rectus abdominis compared to traditional crunches.

The Physiological Foundation of Core Strength

Core strength extends beyond aesthetic considerations to encompass functional performance, spinal health, and metabolic efficiency. The deep core musculature, including the transverse abdominis, multifidus, pelvic floor, and diaphragm, forms an integrated pressure system that stabilizes the spine during movement.

When these muscles contract coordinately, they increase intra-abdominal pressure, creating a rigid cylinder that protects vertebral structures from excessive loading. This mechanism proves essential during lifting, rotational activities, and impact absorption. Weakness in this system correlates with increased injury risk, particularly in the lumbar region.

The lower abdomen also houses significant visceral adipose tissue in many individuals. Unlike subcutaneous fat directly beneath the skin, visceral fat surrounds internal organs and releases inflammatory cytokines linked to metabolic dysfunction. While spot reduction remains physiologically impossible, combining targeted muscle strengthening with overall fat loss through caloric deficit produces visible changes in abdominal composition.

Essential Lower Belly Exercises for Maximum Activation

Reverse Crunches with Controlled Tempo

Lie supine with knees bent at 90 degrees, feet lifted so shins parallel the floor. Place hands beside hips or under the lower back for support. Exhale forcefully while lifting the hips off the ground, bringing knees toward the chest through posterior pelvic tilt. The movement should be small and controlled—only 2 to 4 inches of hip elevation. Lower with control over 3 seconds. Perform 3 sets of 12-15 repetitions.

The key technical element involves initiating movement from the lower abdominals rather than using momentum from the legs. Many practitioners make the mistake of swinging the legs, which transfers tension to the hip flexors and reduces abdominal engagement. Pressing the lower back into the floor throughout the movement ensures proper muscle recruitment.

Dead Bug Variations for Anti-Extension Strength

Begin on your back with arms extended toward the ceiling and knees bent at 90 degrees above hips. Press the lower back firmly into the floor by engaging the transverse abdominis. Slowly extend the right arm overhead while straightening the left leg, hovering the heel 2 inches above the ground. Return to starting position and alternate sides. Complete 3 sets of 10 repetitions per side.

This exercise challenges the core’s ability to resist extension—a critical function for preventing lower back injury during daily activities. The constant tension required to maintain spinal position against moving limbs builds endurance in the deep stabilizers. Adding a 2-second pause at full extension increases difficulty substantially.

Leg Raises with Eccentric Focus

Hang from a pull-up bar with straight arms and engaged shoulders. Begin with knees bent for modified difficulty. Contract the lower abs to tilt the pelvis backward, then lift the knees toward the chest in a controlled motion. The critical phase occurs during the lowering—take 4-5 seconds to return legs to starting position while maintaining posterior pelvic tilt. Perform 3 sets of 8-10 repetitions.

Most training programs emphasize the lifting phase while neglecting eccentric control. Research shows eccentric contractions generate greater muscle damage and subsequent adaptation compared to concentric work. The slow lowering also prevents the ballistic hip flexor dominance that commonly overtakes this movement.

Hollow Body Holds for Isometric Strength

Lie flat with arms extended overhead and legs straight. Press the lower back into the floor by contracting the abdominals and tilting the pelvis. Lift the shoulder blades and legs 6 inches off the ground simultaneously, creating a « hollow » position where only the lower back and hips contact the floor. Hold for 20-60 seconds, breathing steadily. Complete 3-4 sets.

This gymnastic staple develops the sustained tension capacity essential for core stability during complex movements. The position mimics the body alignment required for proper squat mechanics, overhead pressing, and running efficiency. Beginners can modify by bending knees or keeping arms by their sides to reduce leverage.

Progressive Overload Strategies for Continuous Adaptation

The principle of progressive overload applies to core training as rigorously as to other muscle groups. The body adapts to imposed demands by strengthening tissues and improving neural efficiency. Without systematic progression, training plateaus occur within 4-6 weeks.

Volume progression involves increasing total repetitions per session. Begin with 3 sets of 10 repetitions for each exercise, adding 2-3 repetitions per set weekly until reaching 15-20 repetitions. At this threshold, increase difficulty through tempo manipulation or exercise variation rather than continuing to add volume indefinitely.

Tempo manipulation provides sophisticated progression without equipment. A 4-2-2 tempo (4 seconds lowering, 2 seconds pause, 2 seconds lifting) dramatically increases time under tension compared to standard execution. This approach particularly benefits reverse crunches and leg raises where momentum often compromises form.

Introducing instability through tools like exercise balls, suspension trainers, or single-leg variations forces greater stabilizer recruitment. A reverse crunch performed on a stability ball requires constant micro-adjustments to maintain balance, increasing core activation by 15-20% compared to floor-based execution according to electromyographic studies.

Integration with Full-Body Training Protocols

Isolated core work comprises only one element of comprehensive abdominal development. Compound movements like squats, deadlifts, and overhead presses demand intense core stabilization under load, building functional strength that translates to athletic performance and injury prevention.

The squat requires rigid torso maintenance against compressive forces that can exceed 1000 pounds of spinal loading in trained lifters. This necessitates maximal contraction of the entire core musculature, including the lower abdominals working to prevent anterior pelvic tilt as the hips descend. Programming heavy squat variations twice weekly provides substantial indirect core training.

Carries—walking while holding weights in various positions—develop anti-lateral flexion and anti-rotation strength. A farmer’s carry with heavy dumbbells forces the obliques and deep stabilizers to prevent the torso from leaning toward the loaded side. Waiter walks with a single dumbbell overhead create asymmetric loading that challenges the core to maintain vertical alignment.

Rotational exercises like cable woodchops and medicine ball throws train the obliques through their primary function—generating and controlling rotation. These movements require the lower abs to anchor the pelvis while the upper torso rotates, creating a critical stability-mobility relationship.

Nutritional Considerations for Abdominal Definition

Visible abdominal definition requires reducing subcutaneous fat to levels where muscle structure becomes apparent—typically 10-15% body fat for men and 18-22% for women. This outcome depends primarily on sustained caloric deficit rather than specific exercise selection.

Creating a daily deficit of 300-500 calories through reduced intake and increased activity produces approximately 0.5-1 pound of fat loss weekly. This gradual approach preserves lean muscle mass and maintains metabolic rate better than aggressive restriction. Protein intake of 0.7-1 gram per pound of body weight supports muscle retention during dieting phases.

The distribution of macronutrients matters less than total energy balance for fat loss, though higher protein intake (30-35% of calories) increases satiety and has a greater thermic effect than carbohydrates or fats. Fiber intake from vegetables, fruits, and whole grains promotes fullness and supports digestive health—aim for 25-35 grams daily.

Hydration status affects both performance and appearance. Adequate water intake (half your body weight in ounces as a baseline) supports metabolic processes, reduces water retention paradoxically, and maintains training capacity. Chronic dehydration impairs strength, endurance, and cognitive function.

Common Technical Errors and Correction Strategies

Hip flexor dominance represents the most prevalent compensation pattern in lower abdominal training. When the psoas and rectus femoris overpower the abdominals, exercises become leg movements rather than core work. This occurs most frequently in leg raises and reverse crunches.

The correction involves tactile feedback and movement cuing. Place one hand on the lower abdomen and one on the hip flexors during execution. The abdominal muscles should feel hard and engaged while hip flexors remain relatively relaxed. If hip flexors dominate, reduce range of motion, slow the tempo, or regress to an easier variation like dead bugs.

Breath holding during core exercises increases intra-abdominal pressure temporarily but compromises oxygen delivery and creates unsustainable tension. Proper breathing involves exhaling during the concentric (hardest) phase of movement, which naturally enhances core contraction through increased diaphragm activation.

Lower back arching during leg-based movements indicates insufficient abdominal strength to maintain neutral spine. The lower back should remain pressed into the floor or maintain its natural curve without excessive extension. If arching occurs, bend the knees more, reduce range of motion, or choose a regression until strength improves.

Programming Frequency and Recovery Optimization

The abdominal muscles, being primarily slow-twitch and involved in postural control, recover more quickly than larger muscle groups. This allows for higher training frequency—4-5 sessions weekly produces superior results compared to 2-3 sessions when volume per session remains moderate.

A balanced weekly program might include two dedicated core sessions of 20-25 minutes plus three full-body workouts incorporating compound movements with significant core demands. This approach provides adequate stimulus while preventing overtraining and allowing for progressive adaptation.

Recovery between sets matters more for core work than commonly appreciated. While 30-60 seconds suffices for low-intensity movements, exercises performed to momentary muscular failure require 90-120 seconds for adequate ATP resynthesis and neural recovery. Insufficient rest leads to form breakdown and reduced training quality.

Sleep represents the most critical recovery factor, with 7-9 hours supporting optimal hormonal balance, tissue repair, and neural adaptation. Sleep deprivation elevates cortisol, reduces testosterone and growth hormone secretion, and impairs glucose metabolism—all factors that compromise body composition and training progress.

Realistic Timeframes and Expectation Management

Visible changes in abdominal appearance require patience and consistency. Individuals starting with higher body fat percentages need 12-24 weeks of dedicated nutritional management combined with training to reveal muscular definition. Those already relatively lean may see noticeable improvements in 6-8 weeks.

Strength gains manifest more quickly than aesthetic changes. Most practitioners experience improved exercise performance within 2-4 weeks as neural adaptations enhance muscle recruitment efficiency and coordination. This initial progress occurs before significant hypertrophy or fat loss becomes apparent.

Genetic factors influence abdominal development substantially. The shape, symmetry, and insertion points of the rectus abdominis are determined by genetics and cannot be altered through training. Some individuals have visible asymmetry or uneven spacing between the tendinous intersections that create the « six-pack » appearance.

Age affects both the rate of progress and the body fat level required for definition. Hormonal changes, reduced metabolic rate, and decreased muscle mass that accompany aging mean older individuals typically need lower body fat percentages than younger counterparts to achieve similar definition. However, strength improvements remain achievable across the lifespan with appropriate training.

Conclusion

Effective lower belly training combines targeted exercises emphasizing posterior pelvic tilt and controlled tempo with progressive overload strategies and comprehensive nutritional management. The integration of isolation movements like reverse crunches and leg raises with compound lifts creates synergistic development of both muscular strength and aesthetic appearance. While genetic factors and body composition determine ultimate outcomes, consistent application of evidence-based programming produces measurable improvements in core stability, functional performance, and abdominal definition across diverse populations.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional advice.

Source: American Council on Exercise (ACE) – Research on abdominal muscle activation patterns and core training protocols; National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM) guidelines on progressive resistance training and core stabilization.