Discover the science-backed technique to restore your oven’s shine without harsh scrubbing. This proven method combines common household ingredients to break down carbonized grease through chemical action, delivering professional results with minimal physical effort.

Understanding Oven Grime: The Chemistry Behind the Buildup

Oven residue consists primarily of polymerized fats and carbonized food particles that have undergone thermal degradation at high temperatures. When organic matter is exposed to heat cycles between 150°C and 250°C, triglycerides break down and recombine into complex polymeric structures that adhere tenaciously to enamel and metal surfaces. This process, known as pyrolysis, creates layers of hardened carbon deposits that resist simple wiping.

The key to effective oven cleaning lies in reversing this polymerization through alkaline hydrolysis. Sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) creates a mildly alkaline environment with a pH of approximately 8.3, sufficient to saponify fatty acids without damaging protective oven coatings. When combined with the acidic properties of vinegar (acetic acid, pH 2.4), a dual-action mechanism emerges that penetrates carbonized layers while producing carbon dioxide gas that physically lifts debris from surfaces.

The Essential Materials and Their Scientific Functions

For this method, you’ll need baking soda, white vinegar, water, a spray bottle, microfiber cloths, and a plastic scraper or spatula. Each component serves a specific chemical or mechanical purpose in the cleaning process.

Baking soda acts as the primary cleaning agent through its mild abrasive properties and alkaline nature. Its crystalline structure provides gentle mechanical action without scratching enamel surfaces, while its buffering capacity maintains optimal pH for grease dissolution. White vinegar contributes acetic acid, which reacts with alkaline residues and dissolves mineral deposits left by water evaporation during cooking. The effervescent reaction between these two substances creates localized agitation that helps dislodge particles from microscopic surface irregularities.

Microfiber cloths possess electrostatic properties and a structure of split fibers measuring approximately 1/100th the diameter of human hair. This configuration allows them to capture particles at the microscopic level rather than simply redistributing them across surfaces. A plastic scraper provides mechanical leverage for stubborn deposits without risking damage to glass or enamel finishes.

Preparation Phase: Optimizing Conditions for Chemical Action

Begin by removing oven racks, thermometer probes, and any loose debris from the interior cavity. This step ensures maximum surface contact between cleaning agents and soiled areas. Room temperature application works adequately, but slightly warming the oven to approximately 50°C (just warm to the touch) can enhance the kinetic energy of molecules, accelerating the saponification reaction. However, avoid excessive heat, as temperatures above 80°C will cause rapid evaporation of water content, preventing sustained chemical action.

Create a paste by mixing half a cup of baking soda with three tablespoons of water, adjusting proportions to achieve a spreadable consistency similar to thick yogurt. The paste should maintain cohesion without being so liquid that it immediately runs down vertical surfaces. This viscosity allows prolonged contact time, which is critical for penetrating multilayered carbon deposits.

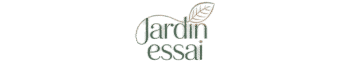

Application Technique: Maximizing Surface Coverage and Contact Time

Using gloved hands or a spatula, spread the baking soda paste evenly across all interior surfaces, focusing particularly on the bottom panel where grease accumulation is typically heaviest. Pay attention to corners and the junction between side walls and the base, as these areas often harbor concentrated deposits. Apply a thicker layer (approximately 3-5 millimeters) on heavily soiled sections, and a thinner coating on areas with light residue.

The paste will initially appear bright white but will gradually darken as it begins interacting with organic compounds. This color change indicates active saponification. For optimal results, allow the paste to remain in contact with surfaces for a minimum of twelve hours, though overnight application (approximately eight to ten hours) typically suffices for moderate buildup. Extended contact times up to twenty-four hours prove beneficial for ovens that haven’t been cleaned in several months.

During this dwell period, avoid opening the oven door frequently, as air circulation can accelerate drying of the paste. If you notice significant drying before the designated time has elapsed, lightly mist the paste with water using a spray bottle to rehydrate it and maintain chemical activity.

The Vinegar Phase: Acid-Base Neutralization and Final Dissolution

After the appropriate dwell time, fill a spray bottle with undiluted white vinegar. Systematically spray the vinegar over all paste-covered surfaces, working in sections to observe the effervescent reaction. The interaction produces sodium acetate, water, and carbon dioxide gas, which manifests as visible fizzing. This gas generation creates microscopic channels through the paste layer, helping to lift loosened debris away from the underlying surface.

Allow the vinegar to react with the baking soda paste for ten to fifteen minutes. During this period, the fizzing will gradually subside as the acid-base reaction approaches completion. The resulting mixture will have a liquefied consistency that incorporates dissolved grease and carbon particles, appearing brown or amber depending on the severity of initial soiling.

Removal Process: Systematic Debris Extraction

Using a damp microfiber cloth, begin wiping away the reacted mixture, starting from the top surfaces and working downward. This approach prevents recontamination of already-cleaned areas by dirty runoff. For stubborn spots where carbonized material remains adhered, apply additional baking soda paste directly to these areas, spray with vinegar, and allow a brief secondary reaction period of five to ten minutes.

A plastic scraper proves invaluable for addressing tenacious deposits without risking surface damage. Hold the scraper at a shallow angle (approximately fifteen to twenty degrees relative to the surface) and apply moderate, consistent pressure. The goal is to shear the bond between the deposit and the enamel rather than gouging or chipping the coating.

Continue wiping with clean, dampened microfiber cloths, frequently rinsing them in warm water to remove accumulated residue. Multiple passes may be necessary to achieve complete cleanliness. For the final wipe-down, use a cloth moistened with plain water to remove any remaining vinegar or baking soda traces, then dry all surfaces with a clean, dry microfiber cloth to prevent water spots.

Addressing the Oven Door and Glass Panel

The oven door’s glass panel requires special attention due to its transparency, which makes streaks and residue highly visible. Many oven doors feature double or triple glazing with a sealed air gap for insulation. If buildup has occurred between glass layers, consult the appliance manual for disassembly instructions, as this typically requires removing the door from its hinges and separating the glass panels.

For external glass surfaces, apply the same baking soda paste method, though a thinner layer suffices due to generally lighter soiling. After the vinegar reaction and initial wiping, a second pass with a glass-cleaning solution or a mixture of equal parts water and vinegar produces a streak-free finish. Wipe in straight lines rather than circular motions to minimize visible streaking, and buff with a dry microfiber cloth for optimal clarity.

Rack Restoration: Extending the Method to Removable Components

Oven racks benefit from an immersion approach that provides three-dimensional contact with cleaning agents. If your sink or bathtub is large enough, place racks inside and sprinkle them liberally with baking soda. Pour or spray vinegar over the entire surface area, ensuring complete coverage. The effervescent action will immediately begin breaking down grease films.

Allow racks to soak for thirty minutes to two hours depending on soiling severity. For heavily encrusted racks, consider adding hot water (approximately 50-60°C) after the initial vinegar reaction to create a dilute cleaning solution that maintains alkalinity. After soaking, scrub with a non-abrasive brush or sponge, rinse thoroughly with hot water, and dry completely before reinstalling.

An alternative method for racks involves wrapping them in ammonia-soaked towels within a sealed plastic bag overnight. Ammonia’s alkaline properties (pH 11-12) provide more aggressive degreasing action, though this approach requires adequate ventilation and careful handling due to ammonia’s respiratory irritant properties.

Maintenance Protocols: Preventing Future Buildup

The frequency of required deep cleaning correlates directly with oven usage patterns and the types of foods prepared. Roasting fatty meats or baking dishes prone to spillage accelerates residue accumulation. Implementing a brief maintenance routine after each use dramatically extends intervals between intensive cleaning sessions.

While the oven is still slightly warm (but safe to touch), wipe interior surfaces with a damp cloth to remove fresh spills before they undergo thermal decomposition. This simple practice prevents the formation of carbonized deposits that require chemical intervention to remove. For immediate spills during cooking, sprinkle salt on the affected area to absorb liquid and prevent smoking; this creates a dry residue easily swept away once the oven cools.

Consider using oven liners on the bottom rack position to catch drips and spills. These reusable silicone or PTFE-coated fiberglass mats withstand high temperatures and can be removed and washed separately, significantly reducing direct soiling of oven surfaces. However, never place liners directly on the oven floor, as they may obstruct airflow and interfere with heating element performance.

Alternative Natural Cleaning Agents and Their Comparative Efficacy

While the baking soda-vinegar combination provides excellent results for most applications, other natural substances offer specific advantages for particular situations. Lemon juice contains citric acid (pH approximately 2.2), slightly more acidic than vinegar, which enhances its capacity to dissolve mineral deposits and soap scum. The d-limonene compounds in lemon oil also possess natural degreasing properties, though these are less concentrated than in commercial citrus-based cleaners.

Salt serves as a mild abrasive for scrubbing without scratching, particularly effective when combined with lemon juice to form a paste for targeting specific spots. However, salt’s crystalline structure is harder than baking soda, requiring more careful application to avoid surface scratches on delicate finishes. Hydrogen peroxide (3% solution) provides oxidative cleaning action and works synergistically with baking soda, though it offers no significant advantage over vinegar for typical oven cleaning applications.

Avoid mixing multiple cleaning agents indiscriminately, as some combinations produce ineffective or potentially hazardous results. For instance, combining vinegar with hydrogen peroxide creates peracetic acid, a compound with antimicrobial properties but also increased corrosivity and respiratory irritant effects. Similarly, never mix ammonia with any acidic cleaner, as this neutralizes the alkalinity that provides ammonia’s cleaning power.

Troubleshooting Persistent Challenges

Certain cleaning scenarios present obstacles that require modified approaches. If the baking soda paste dries completely before the intended dwell time, it loses effectiveness as chemical reactions require an aqueous medium. Rehydrate dried paste by misting with water rather than removing and reapplying, as the paste already in contact with the surface has begun the saponification process.

For oven models with self-cleaning functions, the high-temperature pyrolytic cycle (typically 450-500°C) incinerates organic residues to ash. However, this process generates considerable smoke and odor, requires several hours of operation, and consumes significant energy. The method described here provides comparable results without these drawbacks and proves gentler on oven components, potentially extending appliance longevity.

Discoloration of enamel or stainless steel surfaces sometimes results from heat exposure rather than residue buildup. These thermal stains don’t respond to standard cleaning methods, as they represent metallurgical changes rather than deposited material. Specialized metal polishes containing mild acids and fine abrasives may reduce their visibility, though complete restoration often proves impossible without professional refinishing.

The Environmental and Health Advantages of Natural Cleaning Methods

Commercial oven cleaners typically contain sodium hydroxide (lye) at concentrations producing pH values of 13 or higher, along with surfactants, solvents, and propellants. While highly effective at dissolving organic matter, these formulations pose significant risks including chemical burns to skin and eyes, respiratory tract irritation, and environmental contamination when rinsed down drains.

The baking soda and vinegar method eliminates these hazards while achieving comparable cleaning performance through milder chemical mechanisms. Both substances have GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status from regulatory agencies for food contact applications, meaning residual traces pose no health concerns even in an appliance used for food preparation. The byproducts of their reaction—sodium acetate, water, and carbon dioxide—are environmentally benign and biodegradable.

From a sustainability perspective, purchasing bulk quantities of baking soda and vinegar proves significantly more economical than specialized cleaning products, while reducing packaging waste. A five-pound box of baking soda and a gallon of vinegar cost a fraction of equivalent aerosol oven cleaners and provide sufficient material for dozens of cleaning sessions.

Professional Techniques for Extreme Cases

Ovens subjected to years of neglect or commercial use may develop carbon deposits exceeding several millimeters in thickness. These extreme cases sometimes benefit from mechanical pretreatment before chemical cleaning. Professional appliance technicians occasionally employ steam cleaning systems that inject superheated vapor (above 100°C) under pressure to soften carbonized layers. Portable handheld steam cleaners designed for household use can approximate this effect, though they operate at lower pressures and temperatures.

Another professional approach involves paste formulations incorporating diatomaceous earth, a naturally occurring sedimentary rock composed of fossilized algae skeletons. Its unique porous structure provides enhanced abrasive action while maintaining surface safety. Mixing diatomaceous earth with baking soda and water creates a paste with superior scrubbing capacity for heavily soiled surfaces, though this modification is rarely necessary for residential ovens maintained with reasonable regularity.

The Science of Surface Protection and Long-Term Care

Oven interiors typically feature porcelain enamel coating, a glass-like material fused to steel substrate at high temperatures. This coating provides resistance to chemical attack, thermal shock, and mechanical abrasion. However, repeated exposure to extreme pH conditions or aggressive scrubbing can gradually degrade the enamel’s smooth finish, creating microscopic roughness that facilitates future soil adhesion.

The mild alkalinity of baking soda and moderate acidity of vinegar operate within safe parameters that clean effectively without compromising enamel integrity. Maintaining this protective coating preserves the oven’s self-cleaning properties—smooth enamel surfaces naturally resist soil adhesion and facilitate easier cleaning. Deep scratches or chips in the enamel expose underlying steel to moisture and organic acids, potentially leading to rust formation that requires professional repair or component replacement.

After thorough cleaning, some practitioners apply a thin layer of vegetable oil to interior surfaces, allowing it to polymerize during the next heating cycle. This creates a temporary seasoning layer similar to that maintained on cast iron cookware, which provides marginal protection against future soiling. However, this practice generates smoke during the initial heating cycle and offers modest benefits that may not justify the inconvenience.

Conclusion

This method transforms a typically arduous chore into a manageable task by leveraging fundamental chemical principles. The extended contact time of alkaline paste followed by acid neutralization accomplishes the heavy lifting, minimizing physical scrubbing while maximizing cleaning efficacy. Regular application of this technique, combined with prompt attention to fresh spills, maintains oven cleanliness with modest time investment. The approach respects both the appliance’s materials and the user’s health, demonstrating that effective cleaning need not rely on harsh commercial formulations. Most ovens respond well to this treatment every three to six months, though individual circumstances vary based on cooking frequency and food types prepared.