Figs represent one of humanity’s oldest cultivated fruits, offering remarkable nutritional density and therapeutic properties that contemporary scientific research continues to validate. These delicate fruits, whether consumed fresh or dried, provide essential minerals, dietary fiber, and bioactive compounds that support cardiovascular health, digestive function, and metabolic regulation through multiple physiological pathways.

Nutritional composition and micronutrient bioavailability

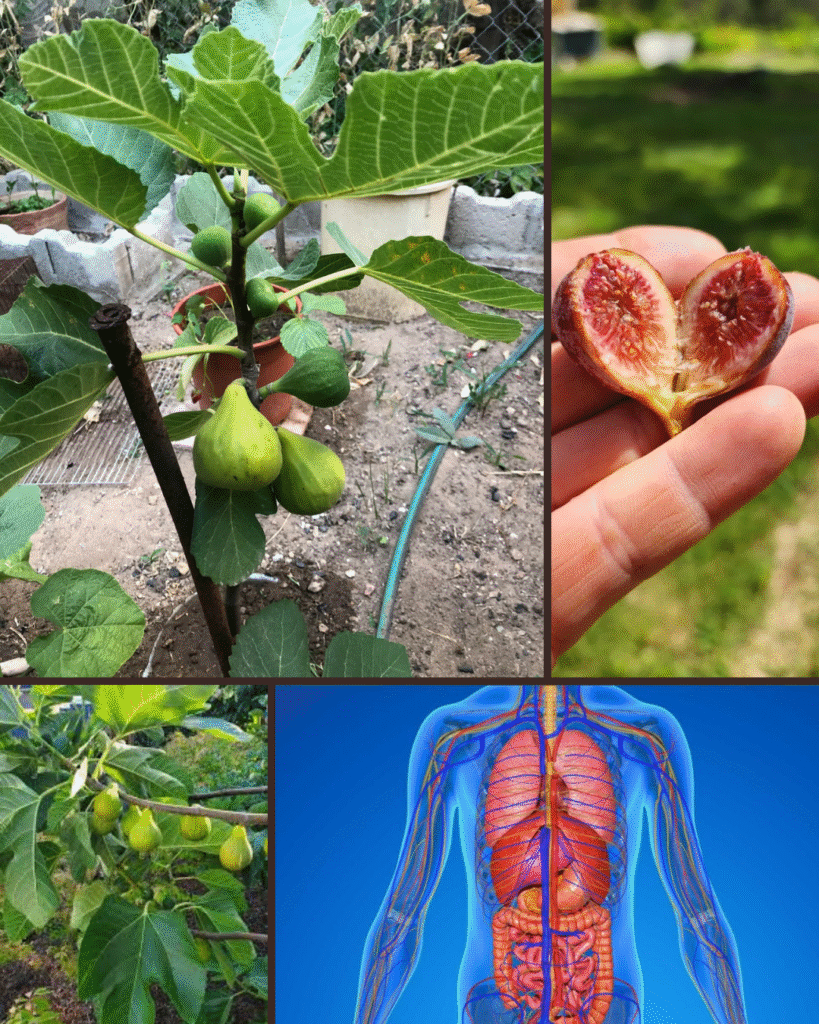

Figs present an exceptionally rich nutritional profile, characterized by high concentrations of essential minerals. A 100-gram portion of dried figs contains approximately 680 mg of potassium, 162 mg of calcium, and 68 mg of magnesium. This mineral density proves particularly significant when considering the bioavailability of these elements.

The calcium present in figs, though plant-derived, demonstrates enhanced intestinal absorption facilitated by the relative absence of oxalic acid, unlike other plant sources such as spinach. The calcium-to-magnesium ratio in figs approaches 2.4:1, a proportion considered optimal for bone mineralization and neuromuscular function.

Figs also contain measurable quantities of non-heme iron (2.03 mg per 100g of dried figs), whose absorption can be enhanced through concurrent consumption of vitamin C sources. This characteristic makes them a pertinent dietary supplement for populations at risk of iron deficiency, particularly menstruating women and individuals following vegetarian dietary patterns.

Dietary fiber and microbiome modulation

The fiber content of figs constitutes one of their most remarkable physiological attributes. Dried figs contain approximately 9.8 grams of fiber per 100 grams, representing roughly 39% of the recommended daily intake. This fibrous fraction comprises both soluble and insoluble components in variable proportions.

Soluble fibers, primarily in the form of pectins and mucilages, exert a demonstrated prebiotic effect. These non-digestible polysaccharides undergo colonic fermentation by anaerobic bacteria, generating short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. Butyrate, in particular, plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and possesses local anti-inflammatory properties.

The insoluble fibers present in figs increase fecal bulk volume and accelerate intestinal transit. This mechanism proves beneficial for preventing chronic constipation, a condition affecting approximately 16% of the global adult population. The gentle laxative effect of figs results from this volumetric action combined with the presence of natural osmotic compounds.

Phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties

Figs contain a diversity of phenolic compounds with significant antioxidant properties. Phytochemical analysis reveals the presence of phenolic acids (gallic acid, chlorogenic acid), flavonoids (rutin, quercetin), and anthocyanins, particularly concentrated in dark-skinned varieties.

These bioactive molecules exhibit measurable free radical scavenging activity through various in vitro assays (DPPH, ABTS, ORAC). The total antioxidant capacity of fresh figs varies by variety but generally ranges between 2 and 4 mmol Trolox equivalents per 100 grams. This antioxidant activity potentially contributes to cellular protection against oxidative stress, a factor implicated in cellular aging and various chronic pathologies.

Fig polyphenols also demonstrate enzymatic inhibition capacity, notably against α-glucosidase and α-amylase. This inhibition slows the degradation of complex carbohydrates into absorbable monosaccharides, thereby modulating the postprandial glycemic response. This mechanism presents particular interest in the context of glycemic management for individuals with insulin resistance.

Cardiovascular regulation and lipid metabolism

The impact of figs on cardiovascular health operates through several physiological mechanisms. The high potassium content contributes to blood pressure regulation through competitive antagonism with sodium at the transmembrane ion transport level. Observational studies suggest that increasing potassium intake by 1000 mg per day associates with a 3-5 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure among hypertensive individuals.

The soluble fibers present in figs interfere with intestinal cholesterol absorption and promote biliary excretion of bile acids. This mechanism forces hepatic neosynthesis of bile acids from circulating cholesterol, thereby reducing plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations. Clinical studies have demonstrated that regular consumption of fiber-rich fruits can reduce LDL cholesterol by 5 to 10%.

Figs also contain phytosterols, compounds structurally similar to cholesterol that compete at intestinal transporter sites, limiting absorption of both dietary and biliary cholesterol. Although phytosterol concentrations in figs are modest compared to nuts or vegetable oils, they nonetheless contribute to the overall lipid-lowering effect of these fruits.

Glycemic index and insulin response

Despite their natural content of simple sugars (fructose, glucose, sucrose), figs present a moderate glycemic index, generally situated between 51 and 61 depending on maturity and preparation method. This relatively moderate value is explained by the significant presence of fibers that slow intestinal carbohydrate absorption.

Glycemic load, a parameter integrating both glycemic index and quantity of carbohydrates consumed, must be considered when incorporating figs into a carbohydrate-controlled dietary regimen. A portion of three dried figs (approximately 40g) generates an approximate glycemic load of 16, considered moderate according to standardized nutritional classifications.

Fresh figs present a lower glycemic impact than their dried counterparts due to their high water content (79%) which dilutes carbohydrate concentration. For diabetic or prediabetic individuals, consuming fresh figs in controlled portions, ideally combined with protein or lipid sources, optimizes postprandial glycemic response.

Bone mineralization and calcium homeostasis

The contribution of figs to bone health operates through several complementary metabolic pathways. Beyond their direct calcium provision, figs contain magnesium and potassium, two minerals essential to bone matrix and calcium homeostasis regulation.

Magnesium participates in over 300 enzymatic reactions, including those involved in hydroxyapatite formation, the principal mineral component of bone. Magnesium deficiency compromises osteoblastic differentiation and alters hydroxyapatite crystallization, thereby weakening bone microarchitecture. Figs, with their significant magnesium content, participate in maintaining this mineral equilibrium.

Potassium exerts an alkalinizing effect that neutralizes the acid load of modern diets, typically rich in animal proteins and refined cereals. This neutralization reduces compensatory bone resorption that occurs when the organism mobilizes bone minerals to buffer metabolic acidity. Epidemiological studies have established a positive correlation between dietary potassium intake and bone mineral density, particularly among postmenopausal populations.

Secondary bioactive compounds and biological activities

Beyond classical macronutrients and micronutrients, figs contain various bioactive molecules with emerging physiological effects. Coumarins, present in variable concentrations according to cultivars, demonstrate anticoagulant and vasodilatory properties in vitro, though their clinical significance at dietary doses remains to be fully elucidated.

Ficins, proteolytic enzymes naturally present in fig tree latex and in lower concentrations in the fruits, possess digestive properties facilitating dietary protein degradation. This enzymatic activity partially explains the traditional use of figs as digestive aids, particularly after protein-rich meals.

Benzaldehydes and furanocoumarins identified in figs present antimicrobial activity against certain bacterial and fungal strains. These compounds contribute to the plant’s natural defense mechanisms and may exert beneficial effects on the human intestinal microbiota by selectively modulating certain microbial populations.

Practical considerations and dietary integration

Optimal incorporation of figs into daily nutrition requires consideration of different available forms and their respective nutritional characteristics. Fresh figs, seasonally available, offer lower caloric density (74 kcal/100g) compared to dried figs (249 kcal/100g), owing to their high water content.

To maximize nutritional benefits, a daily portion of 2-3 fresh figs or 2-3 dried figs proves appropriate for most individuals. This quantity provides approximately 3-4 grams of fiber while maintaining reasonable caloric and glycemic intake. Individuals following carbohydrate-restrictive diets should adjust these portions according to their specific metabolic objectives.

Dried figs present the advantage of prolonged conservation and constant annual availability. However, one should verify the absence of additives such as sulfites, sometimes used as preserving agents, to which certain individuals manifest hypersensitivity. Organically sun-dried figs represent the purest option, free from post-harvest chemical treatments.

Medicinal interactions and precautions

Although generally considered safe, figs may interact with certain pharmacological treatments. Their elevated vitamin K content, though modest compared to leafy green vegetables, necessitates monitoring in patients on vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants (warfarin). Stable and regular consumption, however, minimizes INR fluctuations.

The potassium content of figs requires particular attention among individuals suffering from chronic kidney insufficiency, for whom potassium homeostasis regulation proves compromised. Excessive serum potassium accumulation (hyperkalemia) can engender potentially serious cardiac arrhythmias. These patients should consult their nephrologist before substantially increasing their consumption of potassium-rich fruits.

Figs also possess a laxative effect which, though generally beneficial, may prove excessive with substantial consumption, particularly among individuals presenting irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea predominance. Progressive introduction allows evaluation of individual tolerance and adjustment of quantities accordingly.

Agronomic perspectives and sustainability

Cultivation of the fig tree (Ficus carica) presents notable environmental sustainability characteristics. This fruit tree demonstrates remarkable drought resistance through its deep root system and xerophytic adaptation mechanisms. This hydric tolerance positions the fig tree as a potentially resilient crop facing climate change and water resource scarcity scenarios.

Fig trees require relatively few agrochemical inputs compared to other intensive fruit crops. Their natural resistance to numerous pathogens and pests limits the necessity for pesticide applications. This characteristic aligns with sustainable agriculture principles and reduction of the ecological footprint of food production systems.

The varietal diversity of figs, estimated at over 700 cultivars across Mediterranean and subtropical regions, represents precious genetic patrimony. This biodiversity offers a reservoir of genetic adaptations potentially exploitable for developing varieties optimized according to specific nutritional, organoleptic, or agronomic criteria.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional advice.